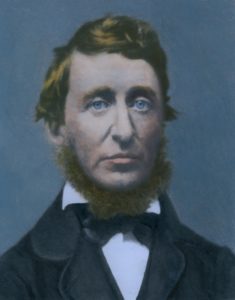

He’s Two Hundred and Not In A Hurry

Do you have a full plate of activities today, a long to-do list? Are you focused on accomplishments?

Then this guy’s approach to life might seem a bit odd:

I think that I cannot preserve my health and spirits, unless I spend four hours a day at least—and it is commonly more than that—sauntering through the woods and over the hills and fields, absolutely free from all worldly engagements.

This proud wanderer just turned 200 a week ago; well, in a manner of speaking he did. In fact he lived just 45 years (oh, to be 45 again!) but his writing keeps resonating with us, as if it were sending out ripples on a pond– Walden Pond, to be precise.

When my husband and his fellow paddlers concluded the River of Life Pilgrimage last week, I had Henry David Thoreau on my mind. He would have loved the spirit of that journey; what they did in canoes—going at a fairly leisurely pace for about four hours a day in fact— was much like the kind of “sauntering” he advocates in the essay I quoted from.

The piece is called, simply, “Walking” and it was first published by The Atlantic in 1861, the year Thoreau died. I don’t know about you, but most of the essays I read don’t run 20 single-spaced pages. This thing goes on and on, meandering through topics much like a river makes its way eventually to the sea. He loves to go from the abstract to the very particular, backing up a claim with a personal experience. Here’s one of my favorite examples: “Methinks we might elevate ourselves a little more. We might climb a tree, at least. I found my account in climbing a tree once. It was a tall white pine…”

Not wanting to give you just breadcrumbs, I offer up the whole essay here when you choose to set aside those pressing tasks or, if you’re unlike me, you get them all done.

We all know the single most famous idea; it comes about smack in the middle. These words that have become a mantra for the Sierra Club and the title of a famous coffee-table book of Eliot Porter’s photography are actually just the last part of a longer sentence.

The West of which I speak is but another name for the Wild; and what I have been preparing to say is, that in Wildness is the preservation of the World.

AH! Only took him about 10 pages to say it, but the line is a keeper, for sure. And, dare I say, also a money-maker. A short Google search will take you soon to the wonderfully ironic “Shop at Walden Pond.”

But with drops of river water practically still in our household, I want to take you back to the beginning of this essay to consider for a moment how Thoreau thinks of his everyday jaunts through the woods. Here is the entire second paragraph:

I have met with but one or two persons in the course of my life who understood the art of Walking, that is, of taking walks—who had a genius, so to speak, for sauntering, which word is beautifully derived “from idle people who roved about the country, in the Middle Ages, and asked charity, under pretense of going a la SainteTerre,” to the Holy Land, till the children exclaimed, “There goes a Sainte-Terrer,” a Saunterer, a Holy-Lander. They who never go to the Holy Land in their walks, as they pretend, are indeed mere idlers and vagabonds; but they who do go there are saunterers in the good sense, such as I mean. Some, however, would derive the word from sans terre without land or a home, which, therefore, in the good sense, will mean, having no particular home, but equally at home everywhere. For this is the secret of successful sauntering. He who sits still in a house all the time may be the greatest vagrant of all; but the saunterer, in the good sense, is no more vagrant than the meandering river, which is all the while sedulously seeking the shortest course to the sea. But I prefer the first, which, indeed, is the most probable derivation. For every walk is a sort of crusade, preached by some Peter the Hermit in us, to go forth and reconquer this Holy Land from the hands of the Infidels.

Wow. Sure wish I’d been able to strengthen my spirits with this back a bunch of years ago when my younger son took off ahead of me on what was supposed to be a run together (definitely the final one). As he disappeared from view in a long-legged way, he turned around and said, “Mom, you’re practically WALKING!”

Come to find out, from this essay, that on this particular day and most all others too I was going even faster than Henry David would’ve gone in his “successful sauntering.” For the rest of the summer, I’m eager to see how this enlightened view might affect my hiking, biking, swimming (not to mention my companions in same). In truth, to get that coveted endorphin rush, I do still believe there is no substitute for the joy that a full-out sprint can bring. But balancing the paces sounds like a good idea, too.

I’ll leave you to ponder who, in his portrayal, the “Infidels” might be. Now there’s a highly charged word. If he’s referring to people who don’t believe sufficiently in protecting the wilderness for all of us and for our children, I’m afraid they are definitely still out there.

After many pages, Thoreau concludes by returning to the remarkable image from his opening:

As we saunter toward the Holy Land, till one day the sun shall shine more brightly than ever he has done, shall perchance shine into our minds and hearts, and light up our whole lives with a great awakening light, as warm and serene and golden as on a bankside in autumn.

For a 200 year old guy, he sure knows how to offer up some fresh beauty.