“Safeguarding Failures”

While it’s not guaranteed that people who attain high positions are worthy of admiration and respect, you can at least hope that whatever earned them their stature offers proof of their capability as well as moral rectitude. That’s what we want in our leaders, after all. Isn’t it?

Sometimes, though, the contrast between the inherent dignity of the office and someone’s unsuitability for or poor performance in the position (perhaps both) can really sock you. There are, of course, degrees of disenchantment. But most of time when this kind of clear demonstration of wrongdoing, or maybe of severe negligence of duty, happens, you’re not sure what to do or think. You recoil, you absorb the loss, you go on.

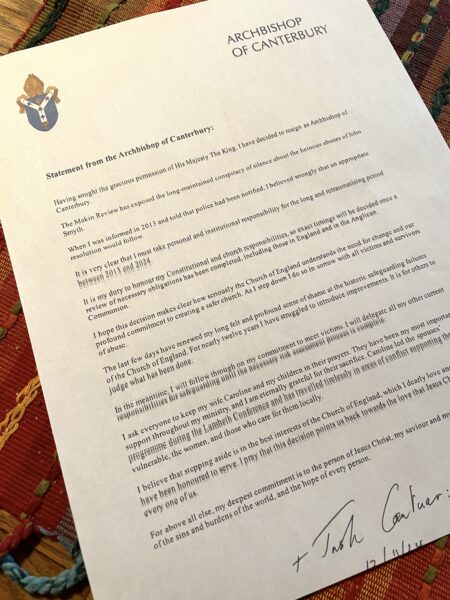

Still reeling from the results of the U.S. election, Rob and I got an unexpected jolt recently in learning about the fall of a religious leader across the pond. It’s not every day that I, someone who started gaining church experience only when I got married, get a letter signed by an Archbishop. Here’s the one-pager that arrived in both of our in-boxes last week.

By the time we read it, we’d already heard the news: The leader of the Anglican Communion resigned because “The Makin Review” had just come out with a scathing report stating unequivocally that the Church of England had not done enough – indeed had done practically nothing at all – in the aftermath of horrible abuses committed by one man in England as well as in Southern Africa, back in the 70s and 80s, even after facts about this abuse came to light in 2013. Yes, the police were contacted, but the Church pretty much turned away from the victims entirely, preferring to hope that, over time, the whole rotten thing would fade away.

You can read more about this (if you can bear it) here: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/12/world/europe/archbishop-canterbury-resigns-abuse-scandal.html#:~:text=The%20archbishop%20of%20Canterbury%2C%20the,ago%20at%20Christian%20summer%20camps.

Here’s how the front pages of two British publications appeared:

We received Welby’s letter directly because this was someone we practically knew. That is to say we were among the hundreds of bishops and spouses who were mingling with Archbishop Justin Welby – his wife Caroline, too –a couple of summers ago at the sprawling, mostly cement block, University of Kent,

in the Southeast corner of England, during a particularly sunny and hot stretch of weather.

When I arrived there in a cab, groggy from the flight and then the long drive from Heathrow, calling Rob en route, I was so relieved that I didn’t have to follow any more instructions about where to go because my sweet husband had run clear across the campus to meet me near our dormitory. I was as thrilled to see him as if he’d been the Archbishop himself; no – wait…more thrilled.

When I got out of that cab, I hadn’t yet glimpsed the enormous hulk of a historic (an understatement) building which was just a mile or so away, over the parched fields, down the hill, into the town of Canterbury. Even if you didn’t get much of a kick from good ol’ Chaucer when you encountered him in school, you would have to be almost insensible not to feel awe at the base of this Cathedral.

Anyway, we weren’t exactly chummy with The Most Reverend Justin Welby Archbishop of Canterbury during those August days of ‘22, but there was a sense of common purpose in the tents and buildings where so many speakers gave voice to all kinds of big aspirations for the role of Church in the world.

The bishops, many of whom came from the continent of Africa (although not from Nigeria, Rwanda and Uganda, where dioceses pointedly boycotted the Conference due to ongoing disagreement about homosexuality – another story) met together under an enormous tent, in a sea of purple. Meanwhile, those of us who were there as spouses had our own designated space, and our own separate program – let’s spell it the British way– “programme.” The Archbishop’s wife was our leader, inviting up women dressed so beautifully in bright colors and beaming smiles, all ready to tell their stories or perform their dances.

In his letter last week, in which he acknowledged his “profound sense of shame at the historic safeguarding failures of the Church of England,” the Archbishop also asked that everyone pray for his family. Besides his wife, he has three daughters. “They have been my most important support throughout my ministry, and I am eternally grateful for their sacrifice.”

I think of that family now, with great sympathy. And I think also of the families of all of the individuals who suffered the abuse perpetrated by the late John Smyth, a barrister who somehow was able to slip by through “safeguarding failures” as an agent of the Church; and of all the families of countless other individuals who also suffered abuse that went undetected for any amount of time.

These days of reckoning just keep coming; we must continue to face them and learn, all of us, to do better. How do you think that can actually happen?